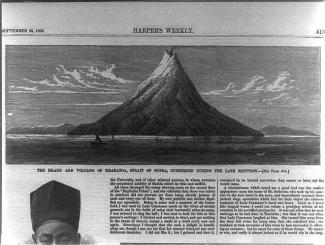

On an early May morning in 1883, the captain of the German warship Elisabeth spotted a cloud of ash and dust rising above the uninhabited island of Krakatau. Little did the captain know that his documentation of this ominous cloud would be one of the first recorded volcanic eruptions from this Indonesian island in at least two centuries.

Over the next two months, commercial vessels and sightseeing ships documented similar spectacles, all of which were associated with explosive noises, churning black clouds and sightings of incandescent ash and pumice. Scientific expeditions were also launched. The local inhabitants on the neighboring islands of Java and Sumatra were so impressed with the display, that a near-festive environment took shape. Only later did they realize that these awe-inspiring displays were a prelude to one of the largest volcanic eruptions in history.

On August 26, 1883, a colossal eruption occurred on Krakatau following a series of explosions. The northern two-thirds of the island collapsed beneath the sea, generating a series of lava, pumice, and ash flows and immense tsunamis that ravaged adjacent coastlines. For those living nearby, the events that began on August 26 would cause the death of approximately 36,000 people and the destruction of hundreds of coastal towns and villages.

Days of Darkness

During the most violent explosion, ash was sent 50 miles (80 kilometers) into the sky. It blanketed 300,000 square miles (800,000 square kilometers), plunging the area into darkness for two and a half days. The ash drifted around the globe, causing halo effects around the moon and sun. The ash also acted as a solar radiation filter, lowering global temperatures by as much as 0.5°C (0.9°F) in the year following the eruption. Temperatures did not return to normal until 1888—five years later.

The final explosion of Krakatau produced the loudest sound ever recorded in modern history, heard across more than 10% of Earth’s surface. Reports of what sounded like distant gunfire were reported from Australia and the island of Mauritius, more than 2,800 miles (4,600 kilometers) from the erupting volcano. Within a few hours, pressure waves traveled several times around the globe. Instruments measured the sudden spikes in Great Britain as well as in America.

As the island collapsed under the sea into the magma chamber, explosions sent as much as 5 cubic miles (21 cubic kilometers) of rock fragments into the air. Much of the remaining island sank into a caldera or volcanic crater, about 3.8 miles (6 kilometers) wide.

The Krakatau eruption spawned a pyroclastic flow. This phenomenon destroys nearly everything in its path. Pyroclastic flows contain a high-density mix of hot lava blocks, pumice, and volcanic ash. Consisting of ash to boulders, flows can travel at speeds greater than 50 miles per hour (80 kilometers per hour). They can knock down, shatter, bury, or carry away nearly all objects and structures in their path. The extreme temperatures of rocks and gas inside pyroclastic flows, generally between 200°C and 700°C (390°F–1300°F), can ignite fires and melt snow and ice.

Even more devastating than the explosion itself was the series of immense tsunamis generated by the event that traveled as far as Hawaii and South America. The largest wave recorded in the Indonesian province of Banten was estimated at 135 feet (41 meters) high, and the following smaller waves destroyed 165 nearby settlements. All vegetation on the islands was stripped bare, homes and structures were completely demolished, and thousands of people in Java and Sumatra perished when they were swept out to sea. Of the 36,000 people who died due to the Krakatau volcano eruption, more than 34,000 deaths were attributed to tsunamis.

Child of Krakatau

Krakatau remained relatively quiet until the 1920s, when volcanic activity began again. Since then, smaller eruptions have created a new cone, Anak Krakatau, or “child of Krakatau” that has risen in the center of the caldera created in 1883.

The offspring of Krakatau grew quickly throughout the 20th century. An eruption of the volcano on December 22, 2018 caused a deadly tsunami. Waves over 260 feet (80 meters) in height were measured at nearby islands that formerly made up the single large volcanic island of Krakatau. At least 437 people died, over 30,000 were injured, and over 30,000 were displaced. The eruption of the “child of Krakatau” is one of the deadliest volcanic eruption events of the 21st century so far.

Despite losing two-thirds of its volume during the 2018 event, Anak Krakatau continued to grow. The volcano erupted again on April 10, 2020, but fortunately, there was no widespread damage. This eruption was captured on April 13, 2020 by the Landsat 8 satellite.

Advances in Disaster Preparedness and Research

Krakatau is referred to as the first scientifically well-recorded and studied eruption of a volcano. Between the time of the Elisabeth captain’s log of clouds of ash to the cataclysmic explosion itself, scientists organized geological expeditions to document the volcano and gather samples of volcanic rocks. The observations made at Krakatau would be of great value to the study of colonization of devastated and newly formed landscapes, such as Mount St. Helens in America.

140 years later, NCEI’s Volcanic Eruptions Database contains a listing of over 500 significant eruptions around the globe. Along with a volcano locations and volcanic ash advisory database, NCEI has assembled a wealth of information about historic volcanoes. Additionally, NCEI has a broad array of tsunami data and information. From historical tsunami events to tide gauge records, NCEI’s tsunami database is full of fascinating and historic information.