On March 12–14, 1993, a massive storm system bore down on nearly half of the U.S. population. Causing approximately $5.5 billion in damages ($11.5 billion in 2022 dollars), America’s “Storm of the Century,” as it would become known, swept from the Deep South all the way up the East Coast. Before the monster storm system developed over the East, it spun up over Texas, bringing damaging winds and hail to southeastern areas of the Lone Star State on the evening of March 11.

With a central pressure usually found in Category 3 hurricanes, the storm eventually spawned tornadoes and left coastal flooding, crippling snow, and bone-chilling cold in its wake. Of the more than 341 weather and climate events with damages exceeding $1 billion since 1980, this storm is the country’s second-most costly winter storm to date.

Visualizing the Storm

Satellites from NOAA and partners provided a bird’s-eye view of the storm’s destructive trek up the U.S. East Coast. Initial development began as the disturbance moved off the Texas coast and into the Gulf of Mexico early on March 12.

Later on March 12, explosive intensification over the Gulf of Mexico became apparent as the storm began to move inland and impact portions of Florida.

The storm intensified and moved very quickly and rapidly transitioned into a powerful winter storm system that devastated much of the East Coast before moving further offshore late on March 14, leaving many Easterners to assess damages and begin to dig out of the historic snowfall. For more visualizations of the evolution and impacts of the 1993 Storm of the Century, see the feature from NESDIS on the storm’s 30th anniversary.

Lots and Lots of Snow

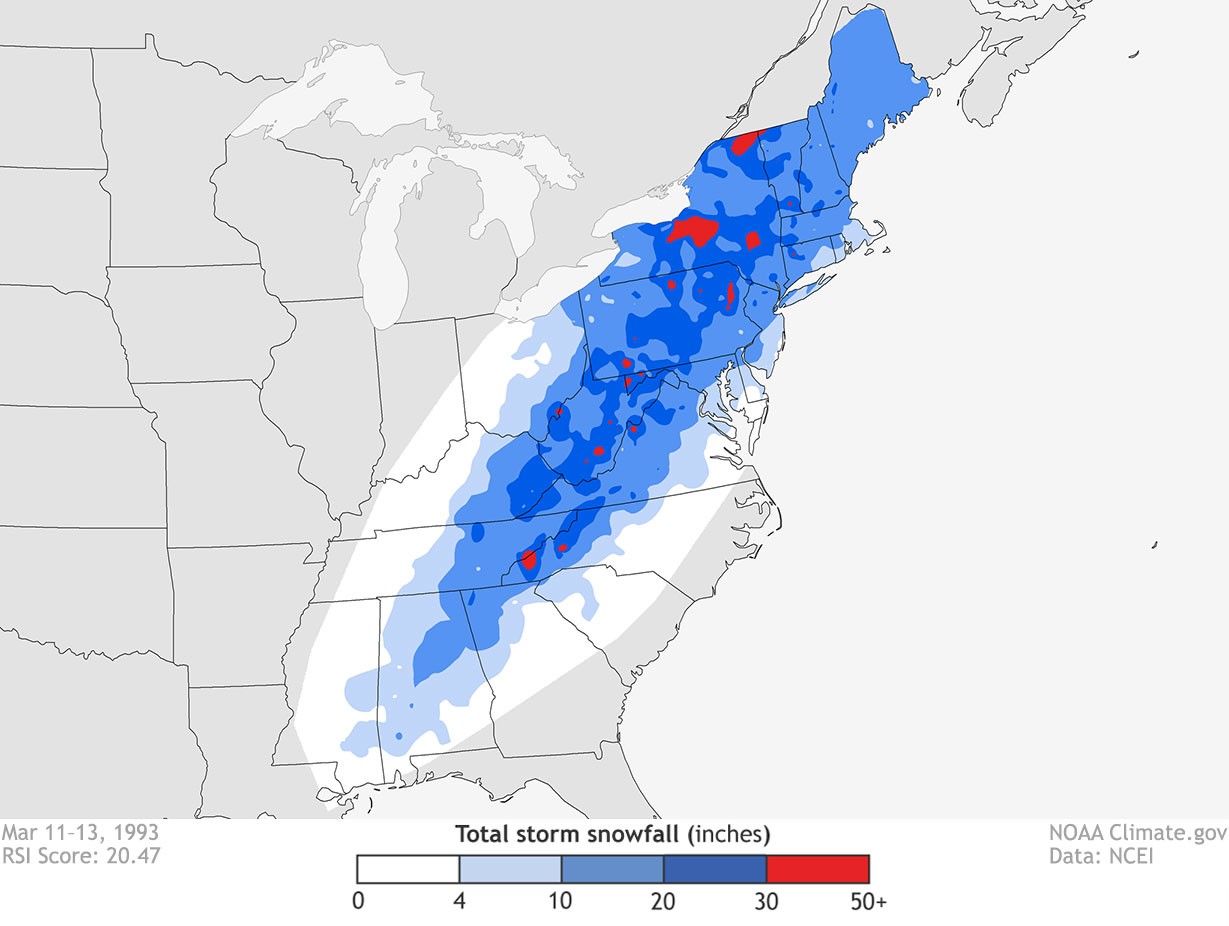

During the height of the storm, snowfall rates of 2–3 inches per hour occurred. New York’s Catskill Mountains along with most of the central and southern Appalachians received at least 2 feet of snow. Wind-driven sleet also fell on parts of the East Coast, with central New Jersey reporting 2.5 inches of sleet on top of 12 inches of snow—creating somewhat of an “ice-cream sandwich” effect. Up to six inches of snow even blanketed portions of the Florida Panhandle.

Some particularly notable snowfall totals included:

- 56 inches at Mount LeConte, Tennessee

- 50 inches at Mount Mitchell, North Carolina, with 14-foot drifts

- 44 inches at Snowshoe, West Virginia

- 43 inches at Syracuse, New York

- 36 inches at Latrobe, Pennsylvania, with 10-foot drifts

The storm ranked as Extreme, or a Category 5, on the Regional Snowfall Index for the Northeast, Southeast, and Ohio Valley regions. Covering more than 550,000 square miles and impacting nearly 120 million people, the Storm of the Century still ranks as one of the worst snowstorms to impact these three regions.

Illustrating the storm’s magnitude, the National Weather Service’s Office of Hydrology estimated the storm’s equivalent total volume of water at 44 million acre-feet. That’s comparable to 40 days’ flow on the Mississippi River at New Orleans—enough water to flood nearly the entire state of Missouri a foot deep.

More than Snow

In addition to the snow, an estimated 15 tornadoes struck Florida, with 44 deaths attributed to either the tornadoes or other severe weather in the state. A 12-foot storm surge also occurred in Taylor County, Florida, resulting in at least seven deaths.

The storm’s high winds were devastating, with at least 15 stations along the East Coast reporting wind gusts of 70 miles per hour or stronger. Dry Tortugas, west of Key West, Florida, recorded a wind gust of 109 miles per hour and Mount Washington, New Hampshire, recorded a gust of 144 miles per hour.

The Impacts to Lives and Livelihoods

The storm’s snowfall isolated thousands of people, especially in the Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia mountains. Workers rescued over 200 hikers from the North Carolina and Tennessee mountains. The National Guard deployed in several counties and cities enforced curfews and declared states of emergency. Overall, more than 270 people across 13 states died because of the storm.

The storm closed nearly all interstate highways from Atlanta northeastward. It also closed every major airport on the East Coast at one time or another—unprecedented at the time, representing the most weather-related flight cancellations in U.S. history up to that point. From Florida to Maine, nearly 10 million people and businesses lost electricity.

From Florida northward, the storm battered the entire eastern coastline, and at least 18 homes fell into the sea on Long Island due to the pounding surf. The storm also damaged about 200 homes along North Carolina’s Outer Banks, making them uninhabitable.

The U.S. Coast Guard rescued more than 160 people at sea in the Atlantic and in the Gulf of Mexico. At least one freighter sank and another 48 people were reported missing at sea.

A NOAA Leader’s Look Back

Former National Weather Service (NWS) Director Louis Uccellini, a lead forecaster at the Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (now the Weather Prediction Center) at the time, recalled forecasting the storm: “So in that middle part of the week, we did start highlighting the potential for a major storm on the East Coast by the weekend, by late Friday and into Saturday. And when we got to day three, we were putting a -- a big storm on the East Coast on the maps, not pulling any punches. That this was going to be a major storm, if not of historic proportions.”

Uccellini also noted the swift and decisive response to the historic forecast by public officials. “What was remarkable to us being inside the forecast was that people started making decisions on it. The New York Turnpike Authority announced that it was going to close the turnpike on Friday night given the amount of snow that we were…forecasting, three to four feet of snow up in upstate New York along the mountains. And then you had states up the chain of the Appalachian Mountains declaring states of emergency even before the snow fell.”

In hindsight, the storm’s forecasts by both computer models and meteorologists marked a major point in NWS prediction of extreme storms and the ability of forecasters to draw public attention to them, from Uccellini’s point of view. “I believe it is a defining moment in our ability to predict these types of extreme events further out in time and do it in a way that people pay attention to it.”

Lessons Learned: Be Prepared

Very powerful storms, like the 1993 Storm of the Century, provide us with important information for analyzing them to better prepare for the future. NCEI’s severe weather data and accompanying analyses provide decision makers, constituents, and stakeholders with the needed tools to ensure the public is well prepared for future devastating storms. For more information on how you can prepare yourself, your family, and your friends for severe weather, visit Ready.gov.